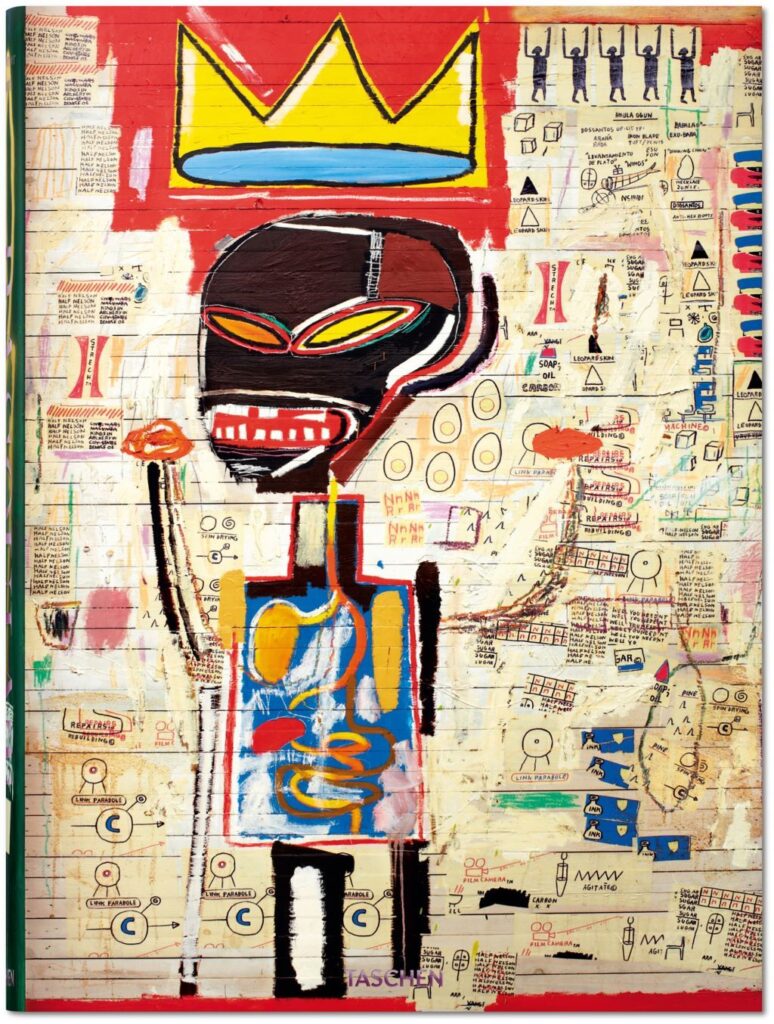

Jean-Michel Basquiat is one of the most famous American artists of the 20th century. Though he lived a tragically short life, dying of a drug overdose at age 27 in 1988, his powerful neo-expressionist paintings have left an indelible mark on the art world. Basquiat’s distinctive visual style is recognizable at a glance. His works are filled with enigmatic symbols, imagery, scrawled text, anatomy, and mythology. But perhaps his most iconic and enduring symbol is the three-pointed crown. This Basquiat Crown meaning appears throughout Basquiat’s body of work, imbuing his paintings with deeper layers of meaning.

The Origins of Basquiat’s Crown

So, where did this crown symbol come from in the first place? We must first look at Basquiat’s background and identity to understand its significance.

Basquiat was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1960. His father was from Haiti, and his mother was Puerto Rican. As a young Black man growing up in America, Basquiat experienced prejudice and racism first-hand. He spoke openly about feeling like an outsider, unseen and unvalued by the white-dominated art establishment.

The crown was Basquiat’s way of subverting this racist narrative. By adorning his Black figures with crowns, he portrayed them as royalty, worthy of honor and praise. The crown challenged society’s failure to recognize the worth of young Black men.

Basquiat also connected the crown to the concept of intellectual power. In medieval times, kings would wear crowns to represent their domain over thought and ideas. Basquiat suggested they possessed knowledge and creative energy by placing crowns on their subjects’ heads. This was his way of elevating his people and declaring intellectual sovereignty.

The Crown as a Recurring Motif

Once Basquiat established the crown as a central symbol, he returned to it throughout his work. The very repetition of the motif speaks to its importance in his artistic vocabulary.

One of his most famous crowned heads is the 1982 painting “Untitled (King Zulu).” Here, Basquiat depicts a Black man in a feathered helmet. The Zulu people of southern Africa were known for their powerful kingdom, which successfully resisted European colonization. Basquiat connects the crown to warriorhood, strength, and resistance by linking his subject to the Zulu.

Basquiat also shows that the crown has been reclaimed from its colonial roots. Traditionally a symbol of empire, the crown is transfigured to represent anti-colonial power and the reclamation of cultural legacy. Basquiat proclaims his people’s right to priority and self-determination.

Other prominent examples include “Charles the First” (1982), which portrays a renowned Black musician crowned in gold. “Untitled” (1982) depicts a regal figure with a halo of flames rising from his head. These flaming crowns may symbolize Basquiat’s Black protagonists’ burning creativity and passion. The crown reinforces themes of fame, self-empowerment, and spiritual illumination throughout these paintings.

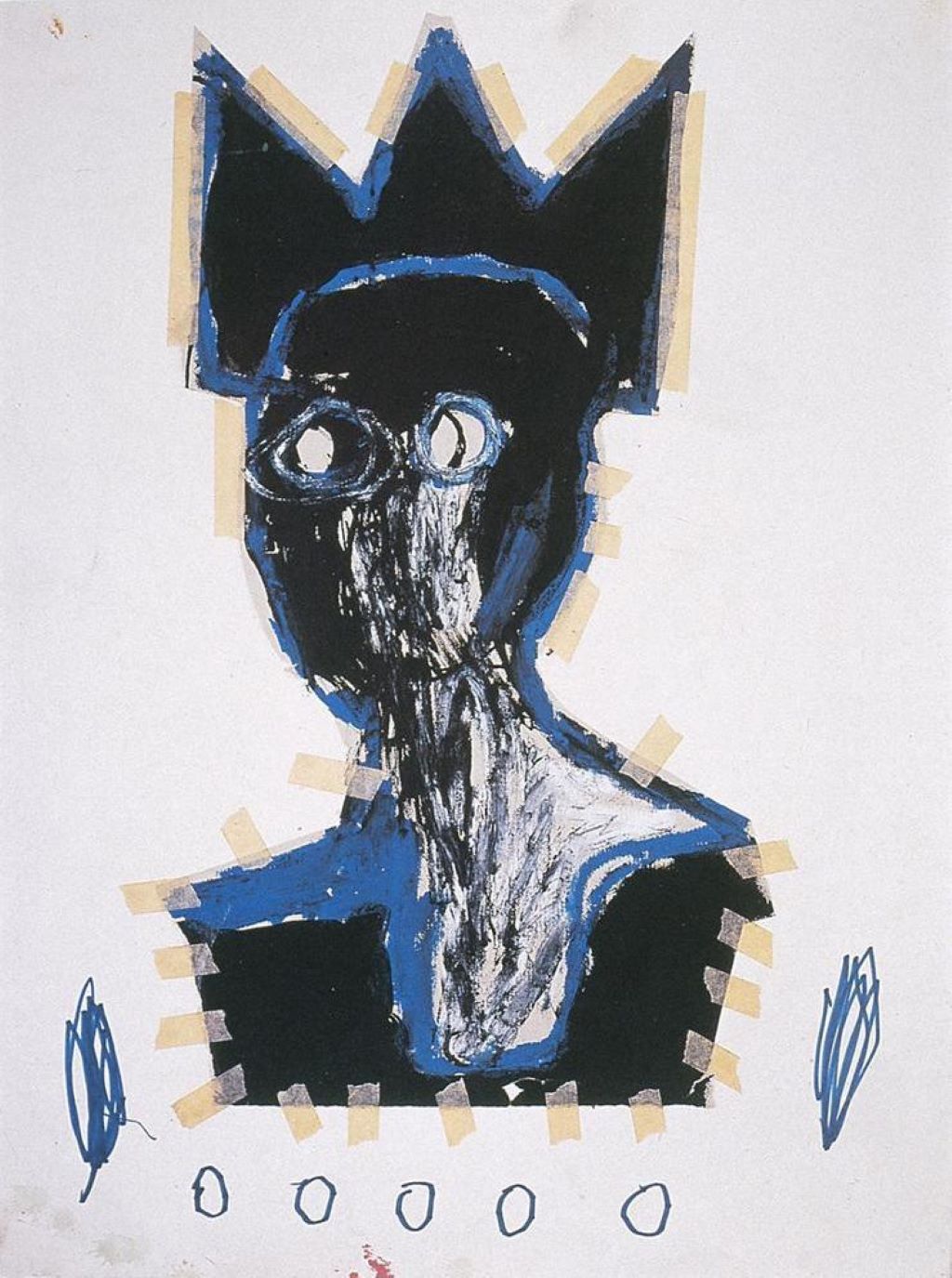

The Triple Crown and Iconic Self-Portraits

Many of Basquiat’s most iconic self-portraits feature him wearing his signature three-pointed crown. This specific triple crown seems to draw from multiple associations.

Firstly, it resembles the triple crown worn by the Pope, the Bishop of Rome. In Catholicism, the three tiers represent the Pope’s jurisdiction over heaven, earth, and purgatory. But instead of claiming religious authority, Basquiat’s triple crown asserts his importance in art and culture.

The three points also evoke childlike associations with fairytale kings and playground castles. Basquiat hints that his power comes from unfettered imagination and creativity. Finally, the triple crown may reference the Holy Trinity in Christianity – the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit unified as one. Basquiat may be placing himself among these “holy three” through the divine nature of his artistic gifts.

Some famous examples of self-portraits include “Self Portrait as a Heel” (1982), where Basquiat crowns himself while painting in his signature Armani suit. “Untitled” (1984) offers a messier depiction, with wild scrawls surrounding Basquiat’s intensely staring face. By repeatedly placing the triple crown on his head, Basquiat claims his artistic kingdom and cements his status as cultural royalty.

The Crown Speaks to Heritage and Legacy

Basquiat also processed his multifaceted cultural inheritance as a Black Latino through this potent symbol. The crown woven African roots, European influences, indigenous Latin American traditions, and Basquiat’s Brooklyn upbringing.

The indigenous Taíno people of the Caribbean decorated their chiefs with tall, feathered crowns to signify status. Basquiat saw his Afro-Caribbean ancestors reflected in these leaders, who ruled through collective power. By taking up their crown, he honored the shared struggle of Black and indigenous peoples against colonial oppression.

The visual worlds of ancient Egypt, Nubia, and medieval Europe also intersect in Basquiat’s crowns. He synthesizes Christian iconography, Egyptian symbols, Western mythology, and African art in his unique visual language. The crown serves as a conduit, channeling the histories of the African diaspora into a singular, defiant emblem of Black excellence.

Above all, the crown represents a legacy. Basquiat never expected to die so young, leaving behind a timeless body of work. By placing crowns on figures of all kinds – athletes, prophets, heroes – he commemorates their lasting impact. Though their physical forms are perishable, their achievements echo indefinitely through time, passed down through generations. In this sense, the crown is Basquiat’s way of sealing his subjects into permanence, reminding us of their enduring imprint upon culture.

The Commercialization of Basquiat’s Crown

Since Basquiat’s meteoric rise in the 1980s, the three-pointed crown has become a globally recognized emblem on apparel, posters, stationery, and more. However, this mass commercialization has sparked debates around cultural appropriation.

While Basquiat endorsed merchandise and helped design apparel bearing his signature motif, many argue against its indiscriminate usage. The crown was deeply personal for Basquiat, symbolizing his people’s struggle and his creative dominance. When separated from this context, the crown risks becoming an empty logo stripped of its original meaning.

Some suggest that his estate exercises tighter control over licensing to ensure the motif’s cultural significance remains intact. Others argue Basquiat wanted his iconography to saturate mass culture, fulfilling his pop art aspirations of melding fine art with consumerism. There are merits to both stances. But when all is considered, we must remember that Basquiat’s crown emerged from the experience of being a young, Black artistic genius in late 20th century America. While we can all appreciate its bold contours and regal associations, preventing appropriation requires actively safeguarding its origins.

Replicating the Basquiat Crown in Art and Media

Basquiat’s signature motif remains a vital creative springboard for many artists. The crown’s visual power lends itself to bold graphics and stylized depictions. But those invoking it would do well first to understand its history.

For instance, the Japanese clothing brand Comme des Garçons incorporated Basquiat’s triple crown into their 2018 Fashion Week collection. However, designer Kei Kagami researched Basquiat’s background, seeking to honor rather than merely mimic his work. Other artists like Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald have also thoughtfully incorporated crowned figures that draw from and expand Basquiat’s legacy.

When it comes to replication, context, and nuance are everything. Dumbing down potent symbols into thoughtless kitsch will always ring hollow. But those who immerse themselves in Basquiat’s world can meaningfully riff on the richness of his iconography. For young Black creatives especially, Basquiat’s crowned heads inform and inspire inventive expressions of self-worth and cultural lineage. By crafting their contemporary crowns, they continue the dialogue Basquiat began.

Conclusion: The Timelessness of Basquiat’s Imagery

In his brief but meteoric career, Jean-Michel Basquiat created a bold, electrifying visual lexicon that still feels ahead. The crown is arguably his most brilliant symbolic masterstroke. At once primal and elegant, this emblem distills volumes into three lines and six points. It speaks mutely yet eloquently of struggle, vindication, majesty, and remembrance.

For Basquiat himself, the crown exuded the very purpose of painting – to permanently crown his people and their triumphs within the canon of art. Exploring the best paintings of Frida Kahlo, we’re reminded of the profound depth found in simplicity, much like the crowns in Basquiat’s work, which, though he considered himself an artistic prince, extend royalty to us all by honoring human potential and containing multitudes under their guise of simplicity.

And so the crowns of Basquiat continue to reign through their paradoxical nature. At once sharply personal yet infinitely expansive, they endure as artifacts of creative fire and immortal possibility. Their intrigue and impact remain timeless.

FAQs

What inspired Basquiat to use crowns in his art?

Basquiat was inspired by the racism and prejudice he experienced as a young Black man in America. The crown represented his desire to uplift and empower Black culture, showing it as royal, honorable, and possessing knowledge.

What does the triple crown symbolize?

The three points of Basquiat’s signature triple crown hint at multiple meanings – the triple crown of the Pope, fairytale castles, and the Holy Trinity. For Basquiat, it signified his importance in the art world, his childlike creativity, and his godlike talents.

How did Basquiat’s Caribbean roots influence the crown?

Basquiat connected the indigenous Taíno people’s chieftain crowns to his Afro-Caribbean lineage. By adopting this symbol, he honored his ancestors’ collective power and struggle against colonialism.

Why is the commercial use of Basquiat’s crown controversial?

When separated from its origins, the crown risks becoming an empty logo stripped of significance. Some argue Basquiat’s estate should limit licensing to prevent cultural appropriation and dilution of meaning.

How can artists thoughtfully incorporate Basquiat’s crown motif today?

Artists who take time to research Basquiat’s background and message can meaningfully riff on his iconography in new contexts. This allows them to continue the cultural dialogue Basquiat started with his crowned heads.